Winning with Quantitative Trading

Quantitative Algorithmic trading is the computerised execution of the financial instruments following the trading strategies that are developed using advanced mathematical models. Quantitative methods are used for carrying out the research, analysing the historical data and using the complex mathematical and statistical models to find the trading opportunities that are profitable.

The algorithm, using the quantitative models, decides on various important aspects of the trade such as the price, timing, and quantity, and executes the trade automatically without human intervention. The algorithmic trading process involves making use of powerful computers to run these complex mathematical models and execute the trade orders.

This involves automating the full process including order generation, submission, and the order execution and provides investors with more efficient executions while lowering transaction costs and the result is improved portfolio performance.

The benefits compared to traditional trading include (among many others):

- Higher efficiency

- Lower commissions

- Anonymity

- Reduced market impact

- More Control over the orders

- Minimum Information Leakage

- Transparency surrounding the order execution for the money manager or investor

- Reduced transaction costs

The mere adoption of algorithmic trading alone does not guarantee better results. It is imperative that the underlying strategy is proactive, robust and extremely well back-tested.

A quantitative algorithmic trading engine will need many robust parts working hand in hand, but at the same time each of them applying their ownquantitative techniques. Some of the key elements required are:

- Investable Universe identification

- Generic factor information

- Clear factor Quality identification

- Factor seasonality

- Investing with conviction and in time

- Exhaustive and un-biased backtesting

One can never over stress the importance of rigorous back-testing, free from any bias, intentional or un-intentional. Back-testing is a popular way to examine the performance of a quantitative trading strategy. It simulates trades of assets utilising historical data of the assets and any other additionalinformation if necessary. One important assumption here is that we could have bought and sold the assets at the realised prices in the past such as daily closing prices, even though this might not have been the case in reality.

A word of caution here is that a high performance in back-testing does in no way guarantee the same results in future. Back-testing is a kind of backward-looking methodology by its very nature and there is no guarantee that the future market will behave like the past. Despite this, the back-testing can still give us enough useful information to understand why one strategy works well and the other doesn’t, depending on various market situations which occurred in history.

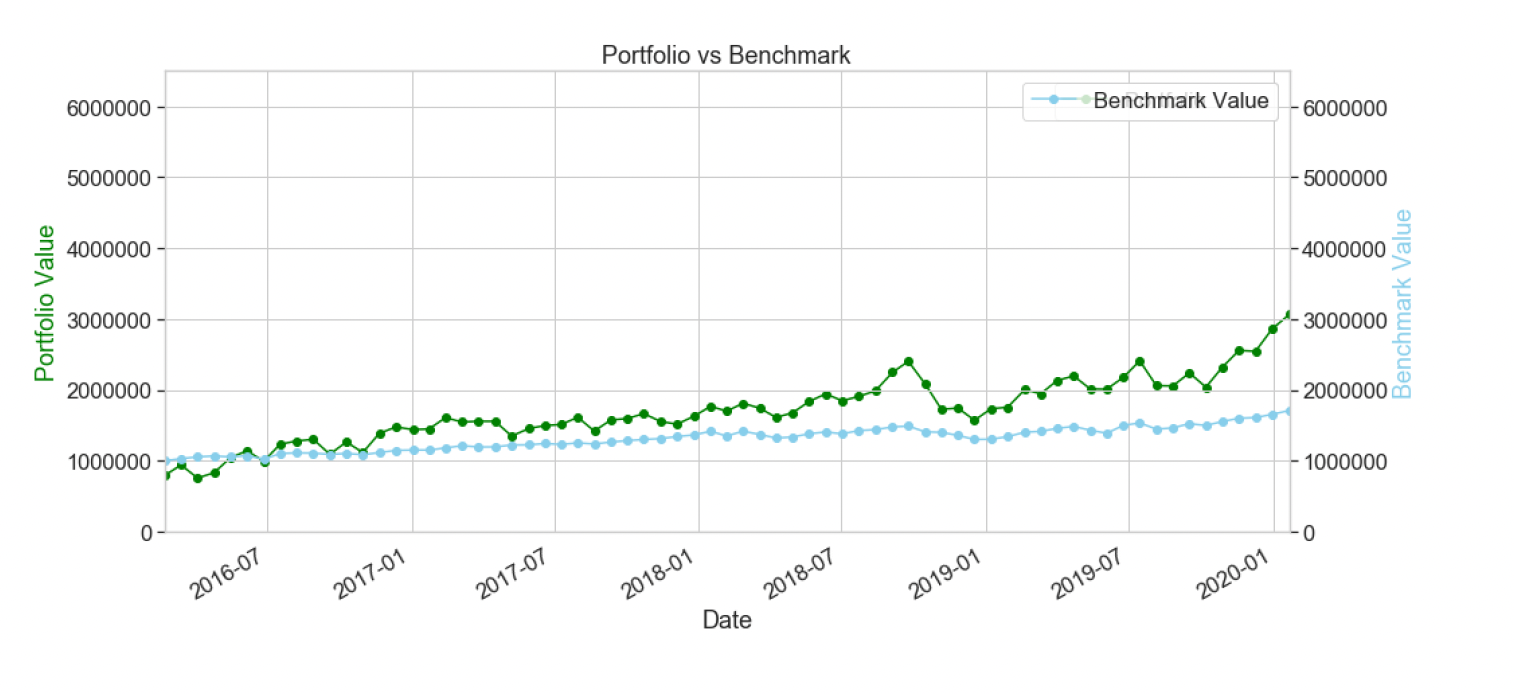

Below is a graph showing the results of an overlapping momentum strategy,where the returns on a portfolio comprising of a maximum of 10 assets at any point are compared to benchmark performance for S&P 100 index, over a period of 4 years from Feb, 2016 to Jan, 2020. The performance of the assets is tracked monthly and, where required, leads to portfolio turnover. Although, it appears that the strategy was quite effective and provided a decent return of over 200% over the tenure but still, apart from other factors that need to be reviewed, including maximum drawdown and the Sharpe ratio, the 4 years period for back-testing is quite small.

Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) documented how strategies of buying recent stock winners and selling recent losers generated significantly higher near-term returns than the market. But, the above strategy presented as example has purely taken long position on the momentum stocks.

We know that momentum exists, but why should such a strong return pattern such as momentum persist?

As an investment strategy, it stands almost in complete denial of, the “efficient market hypothesis” (EMH), one of the central tenets of modern finance. A natural possibility is investor misreaction due to behavioural biases. Jegadeesh and Titman (2011) also suggest that momentum profits arise because of a delayed reaction to firm specific information.

EMH, of course, is the argument that has made index (or “passive”) stockinvesting so incredibly popular over the last 25 years: You can’t outsmart the market, so just own the whole thing. Yet various styles of momentum investing continue to reward their investor practitioners with above-average returns.

Why is quantitative trading becoming increasingly important?

The combination of the behavioural bias and market frictions constantly results in mispriced assets. This arbitrage can often be short lived and if not taken advantage of in short space of time, it is simply opportunity lost. And since humans are flawed decision makers under duress, the trading job is best performed by algorithms that are trained using deep learning and gargantuan sets of data.

The race to higher alpha in most firms often boils down to getting hands on the next valuable source of data. There is a lot of tactical asset allocation alpha to derive from macro-economic and price-volume data. This is exactly why most quantitative fund managers believe that data science is the only way to build a great portfolio management firm today. But building a data science firm needs a sizable investment. Most of the investments are front loaded and cannot be deferred to a time when the fund has raised hundreds of millions of dollars already. Hence an institutional investor needs to think like a venture capital firm and be prepared to invest in the GP of promising managers.

As we have seen, for Investment Management industry, the recent years havebeen full of A.I. advancements, stronger ‘deep learning’ adoption in finance, higher initial setup costs as well as fresh market challenges.

References:

- Jegadeesh, N. and Titman, S., 1993. Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency. The Journal of Finance, 48(1), p.65.

- Jegadeesh, N. and Titman, S., 2011. Momentum. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 3(1), pp.493-509.